Draw to Learn: A Strategy to Learn Abstract Concepts

This project studies how student-generated drawings aid learning of abstract science concepts in a lab setting.

Summary

While visual aids are known to enhance learning by helping process complex information, most educational visuals are provided by instructors rather than created by students. This study investigated whether student-generated drawings could be more effective for learning abstract scientific concepts, those that don’t have a definitive physical form, addressing a gap in existing research which has primarily focused on concrete, observable systems.

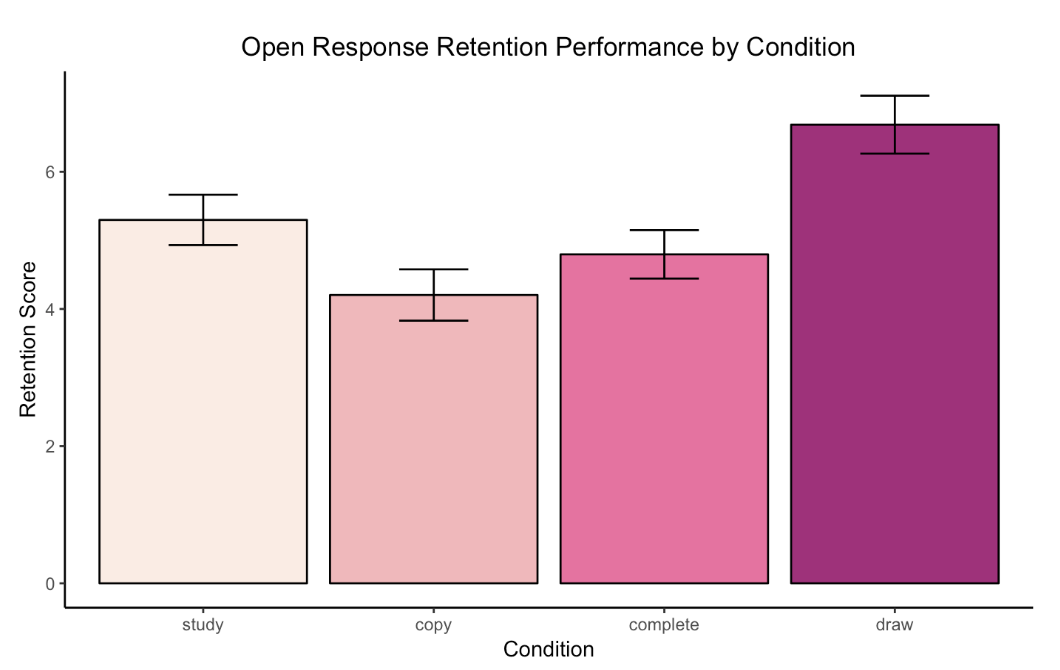

Through two controlled experiments with 213 college students at UC San Diego, we compared four learning conditions: studying provided illustrations, copying existing drawings, completing partial drawings, and creating freeform drawings while learning about abstract concepts like black holes. Results showed that students who created their own drawings scored significantly higher on retention tests ($\bar{x}$ = 6.688, $s$ = 2.93) compared to those who copied illustrations ($\bar{x}$ = 4.204, $s$ = 2.750, $p$ < 0.0001), though this advantage did not extend to knowledge transfer tasks.

Additional analyses revealed that drawing increased study time and engagement with the material, suggesting that the improved retention may be partially attributed to longer exposure to the content. While these findings indicate that drawing can enhance learning of abstract concepts, a laboratory setting is not representative authentic classroom environments where students are more genuinely motivated to learn. Future work should explore the use of drawings to learn abstract science concepts in classroom environments.

Introduction

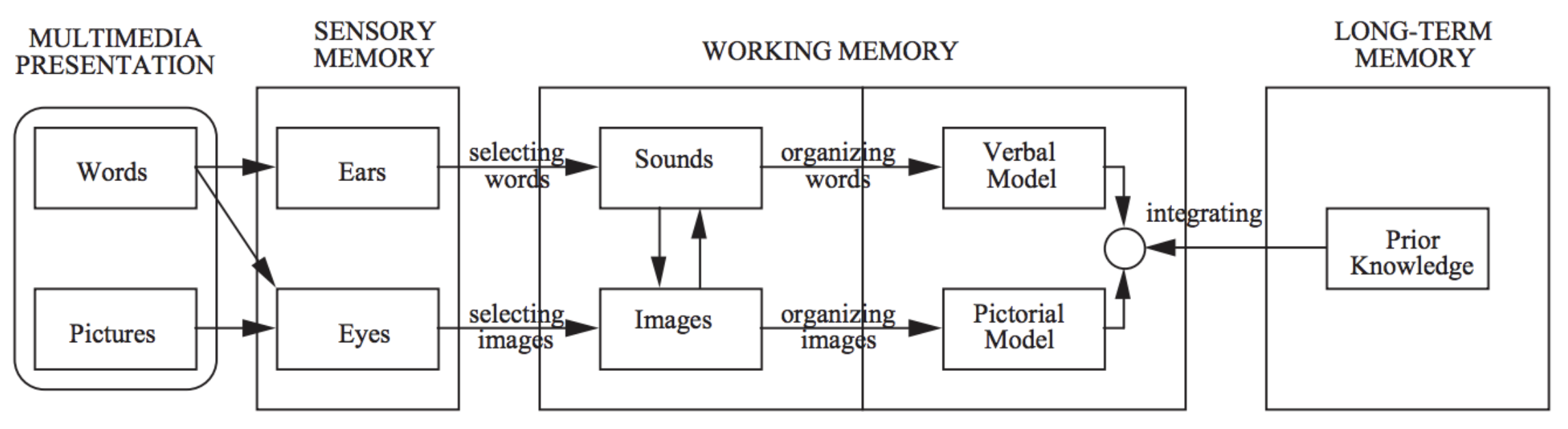

Visual representations are fundamental to learning, serving multiple cognitive functions: they summarize complex information, illustrate spatial relationships, and enhance memory retention

The theoretical foundation for understanding these processes rests on two key cognitive theories. The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning posits that effective learning involves three processes: selecting relevant information, organizing it into coherent representations, and integrating it with existing knowledge

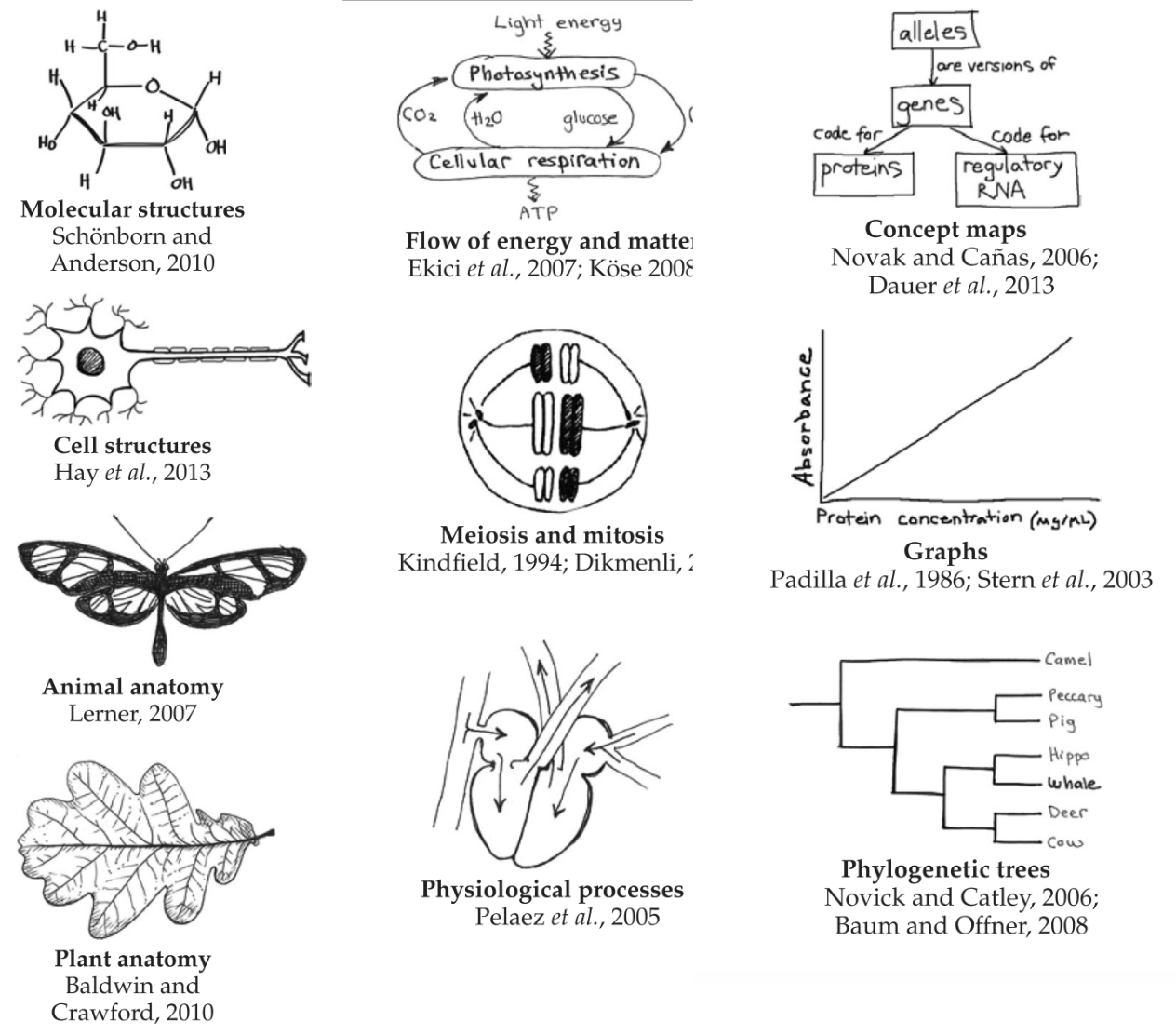

Drawing as a learning strategy presents both opportunities and challenges. Creating drawings can help students identify knowledge gaps and monitor their understanding through self-generated feedback

Most studies on learner-generated drawings focus on concrete, observable systems. However, not all scientific concepts have definitive visual representations. Topics like dark matter, black holes, and natural selection are either theoretical, unfold over long periods, or lack a physical presence. Our research explores whether the efficacy of drawing to learn depends on the content of the lesson.

We hypothesize that drawing will enhance learning of abstract concepts more effectively than concrete ones. For abstract lessons, we expect learning to increase as students generate more of their own drawings. For concrete lessons, we predict that guided drawing will most benefit learning by reducing cognitive demands.

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample of 238 undergraduate students was gathered from the University of California, San Diego Psychology Subject Pool. All participants received partial course credit for their participation. Twenty-five participants were excluded from data analysis, leaving a final sample of 213 participants. Of the 213 participants, 43 identified as male, 165 identified as female, and five identified as non-binary. A majority of participants were in their early twenties with a mean age of 20.27 ($s$ = 1.93 years). Fifty-seven students participated in the study condition, 54 in the copy condition, 54 in the complete condition, and 48 in the draw condition.

Design

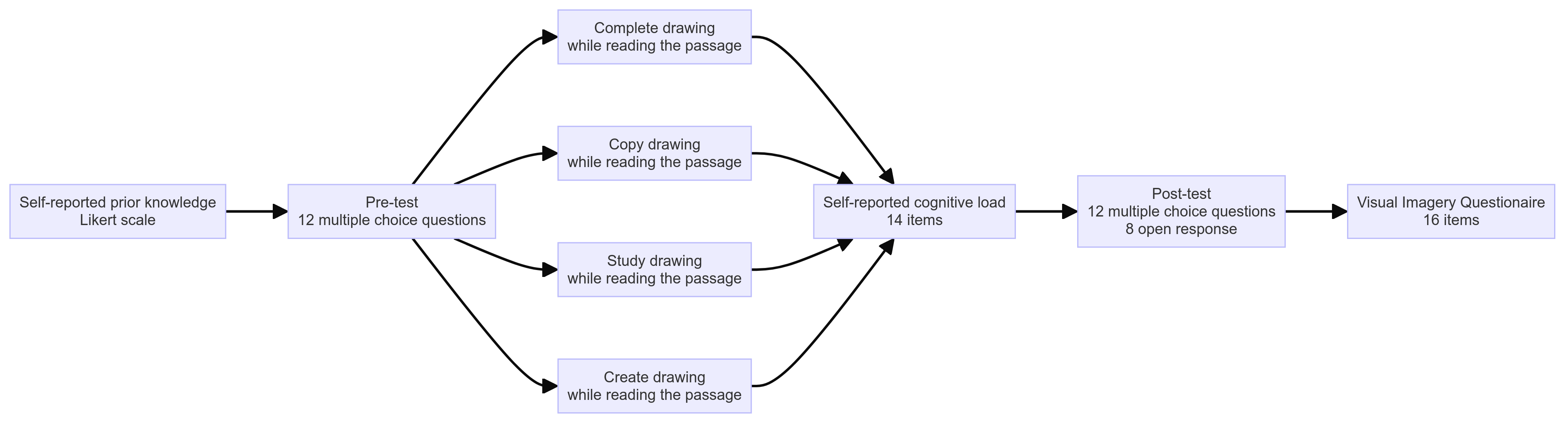

We used a between-subjects design to manipulate participants’ drawing experience and measure their learning from a lesson about black holes. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four drawing conditions, which varied by the degree to which they generated their illustrations: copying a provided illustration (“copy”), completing a partial illustration (“complete”), free drawing their own illustration (“draw”), or a control condition that involved no drawing (“study”). Learning was measured using multiple choice and open response questions designed to assess both the retention and transfer of the lesson content. We also measured participants’ prior knowledge about physics and astronomy, their visual imagery ability, and their cognitive load during the learning activity to use as covariates in our analyses.

Materials

The materials for this study included a Qualtrics survey, a passage about black holes, illustrations to support the passage, passage comprehension tests (multiple choice and open response), and measures of individual differences (prior knowledge, visual imagery ability, cognitive load). All materials were presented to participants via a Qualtrics survey, which they accessed online via desktop computers in a lab setting.

-

Prior Knowledge: Participants self-reported their knowledge and confidence in physics and astronomy using 5-point Likert scales. The knowledge scale ranged from “I know nothing at all” to “I know a great deal,” and the confidence scale ranged from “not confident at all” to “extremely confident.” The prior knowledge score was calculated by multiplying the knowledge and confidence ratings for both subjects and summing the results.

-

Black holes Lesson: All participants read an educational passage about black holes, adapted from The Cosmic Perspective textbook

. The passage was condensed to 11 paragraphs (1607 words) covering the definition, formation, properties, event horizon, singularity, size, and internal structure of black holes. The readability of the passage was measured using the Automated Readability Index (ARI), resulting in an ARI of 11.30, indicating a grade level of 11.6. -

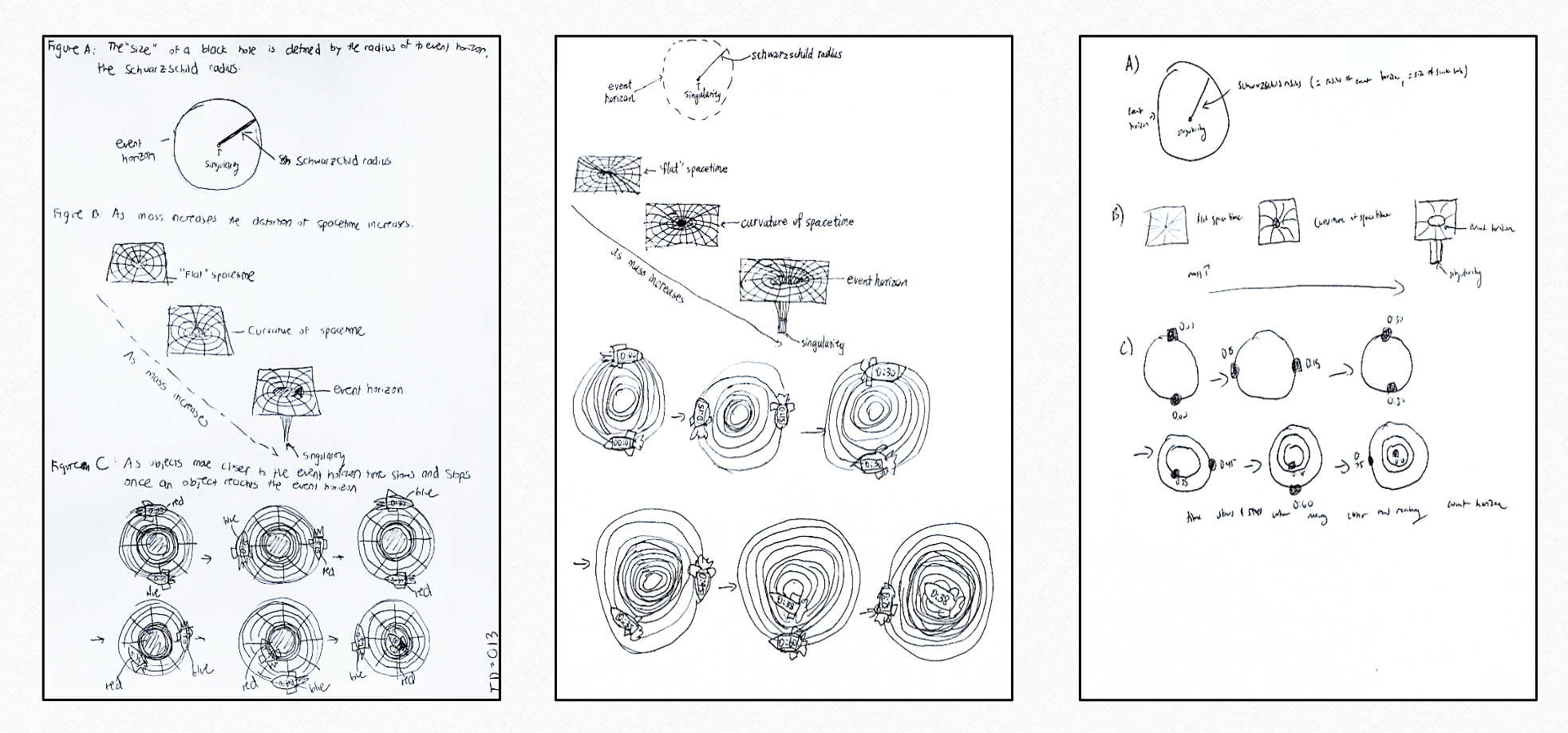

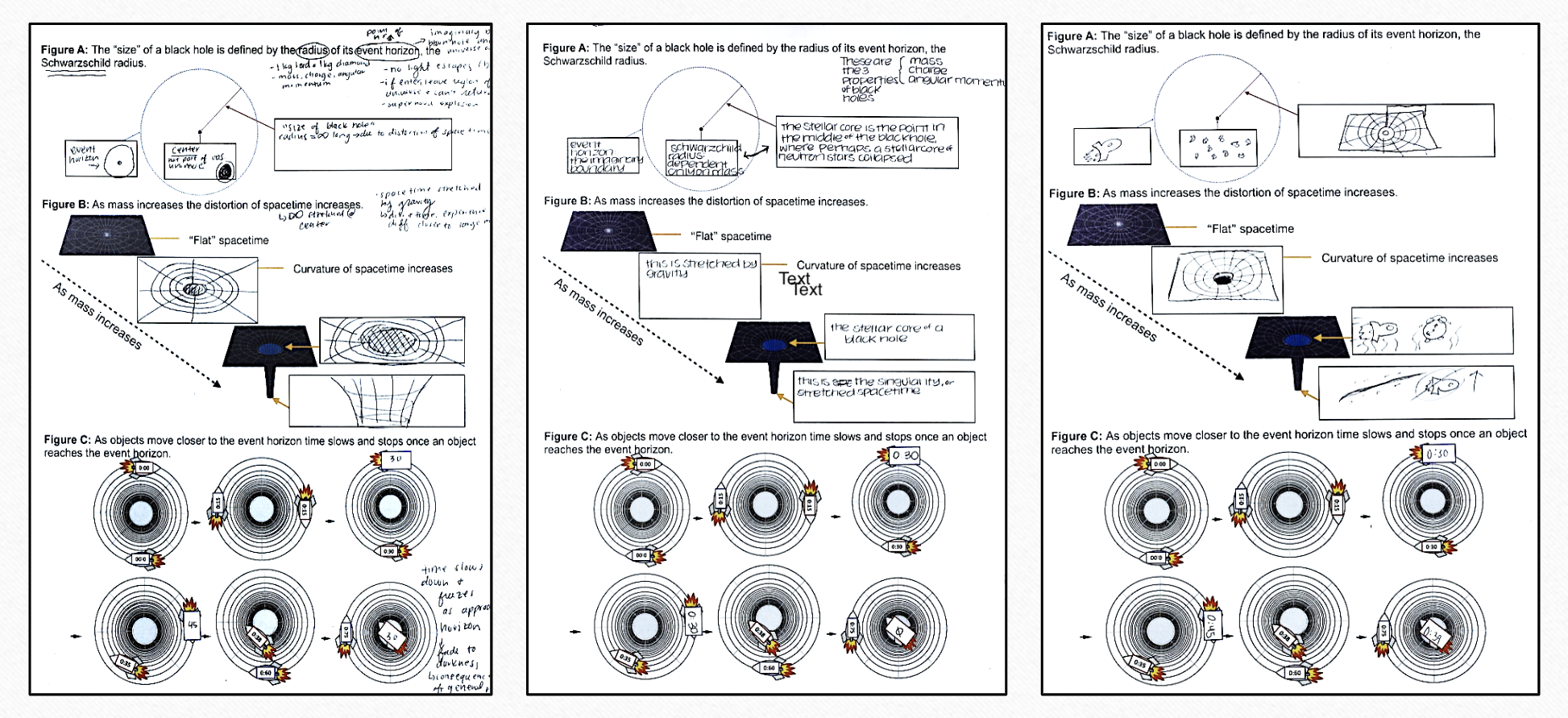

Illustrations: Participants in the copy, study, and complete conditions received illustrations produced using Adobe Photoshop 2019 and Pages. Inspired by The Cosmic Perspective textbook and Pearson Mastering Astronomy platform

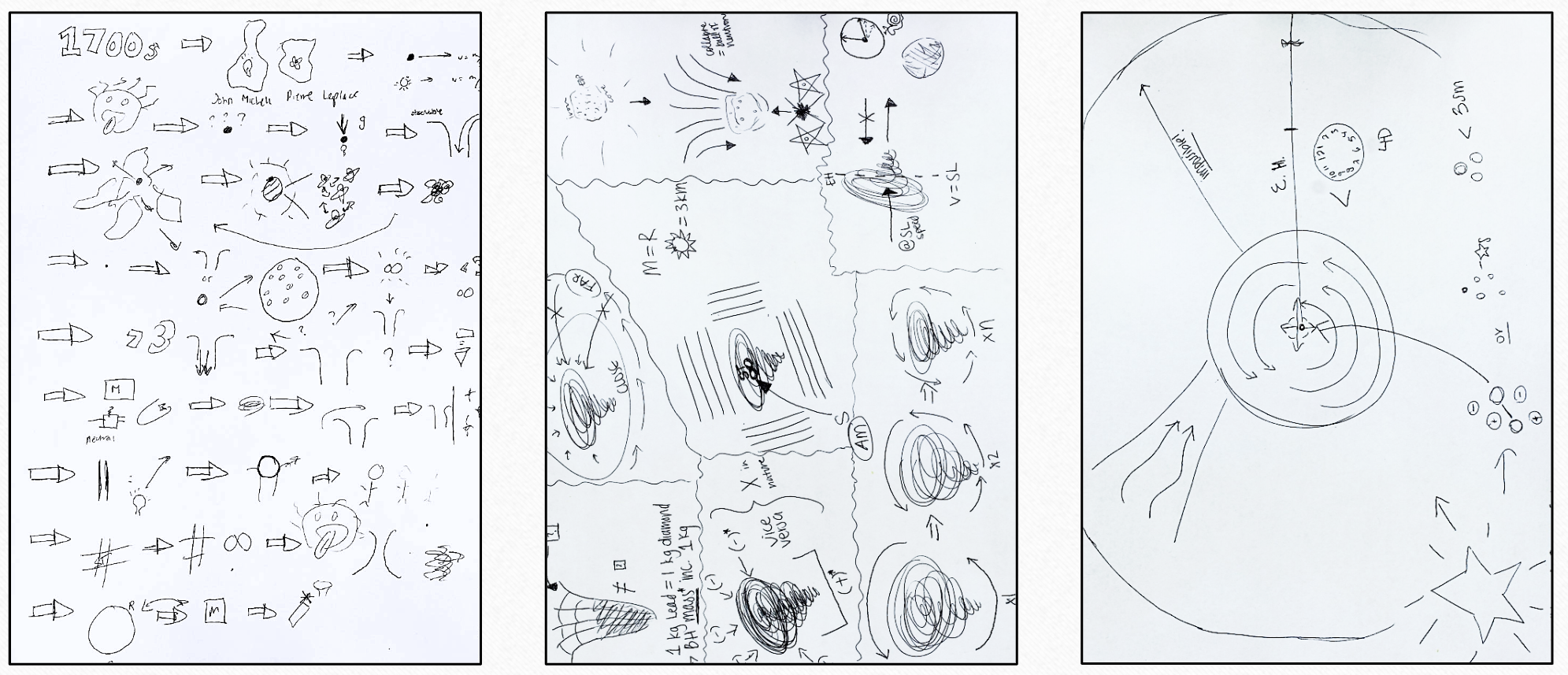

, the illustrations included drawings of black hole features, Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, and spacetime distortion near black holes. Scaffolded illustrations featured key elements masked with empty text boxes. Participants in the drawing condition received blank sheets of paper and pens. -

Passage Comprehension Tests: Three types of tests were developed: two analogous 15-question multiple-choice tests, one 4-question open response retention test, and one 4-question open response transfer test. The multiple-choice tests included 8 perfect analogs and 7 strong pairs of questions. Retention questions asked students to summarize lesson information, while transfer questions required application of knowledge to new scenarios. Answers were scored based on identified idea units, with inter-rater reliability for retention and transfer tests being $r$(212)=0.995, $p$ <0.0001 and $r$(212)=0.798, $p$ <0.0001, respectively.

-

Cognitive Load: Cognitive load was measured using a 10-item instrument assessing intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load

. Participants rated items on a 0 to 10 scale. Examples included “The topics covered in the activity were very complex” (intrinsic load), “The instructions and explanations during the activity were very unclear” (extraneous load), and “The activity really enhanced my understanding of the topics covered” (germane load). Cognitive load was analyzed to determine the impact of visualization strategies on perceived difficulty and mental effort. -

Visual Imagery: Visual imagery ability was assessed using the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), which asks participants to rate the vividness of imagined scenes on a 5-point Likert scale

. The VVIQ was completed once with eyes open.

Results

Planned Analyses

This study examined whether generative illustration activities enhance knowledge retention and transfer in learning about black holes. Of 238 initial participants, 213 were included in the final analysis after applying exclusion criteria for task engagement, attention checks, and study completion.

Baseline assessments showed no significant differences across conditions in visual imagery ability ($\bar{x}$ = 3.761, $s$ = 0.574 on a 5-point scale), prior knowledge in physics and astronomy ($\bar{x}$ = 9.310, $s$ = 6.813 on a 50-point scale), or black hole pre-test scores ($\bar{x}$ = 4.188, $s$ = 1.963 out of 12 points). This established comparable starting points across experimental conditions.

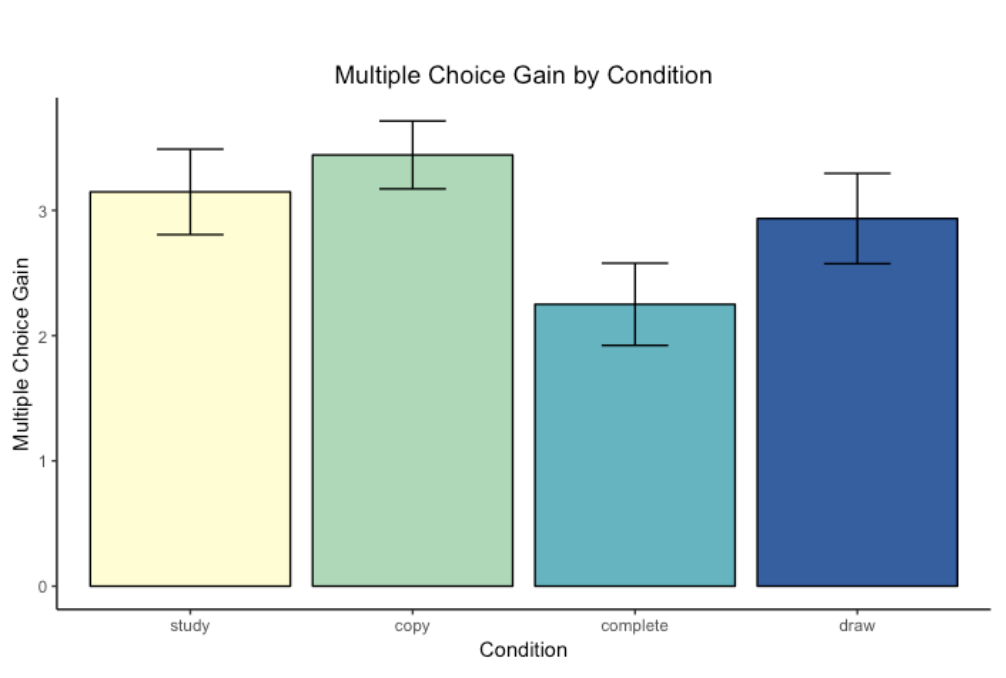

Analysis revealed significant differences in open-response retention scores ($F$(3,209) = 7.41, $p$ < 0.001), with the drawing condition ($\bar{x}$ = 6.688, $s$ = 2.93) significantly outperforming both the copying ($\bar{x}$ = 4.204, $s$ = 2.750, $p$ < 0.0001) and partial illustration conditions ($\bar{x}$ = 4.796, $s$ = 2.595, $p$ = 0.0037). The difference between drawing and study conditions approached significance ($p$ = 0.052). However, no significant differences emerged in multiple-choice gains or transfer scores across conditions.

Exploratory Analyses

Additional analyses were conducted to explore mechanisms by which drawing might enhance learning. We examined reading time, cognitive load, condition enjoyment, and word count:

-

Reading Time: Participants in the drawing condition spent more time engaging with the lesson ($\bar{x}$ = 16.994 min, $s$ = 5.809) compared to other conditions (study, copy, complete), which could contribute to their better performance on the open-response retention test. This is supported by the presence of a significant linear relationship between reading time and open-response retention test scores ($F$(1, 211) = 6.97, $p$ = 0.008).

-

Cognitive Load: We found no overall differences in cognitive load across conditions. However, significant differences were observed in extraneous load ($F$(3,209) = 15.82, $p$ < 0.0001) and germane load ($F$(3,209) = 6.20, $p$ = 0.0005). Participants in the complete condition reported higher extraneous load, while those in the study condition reported higher germane load compared to other groups.

-

Condition Enjoyment: Participants in the study condition enjoyed the activity more ($\bar{x}$ = 3.965/5 Likert scale, $s$ = 0.778) than those in other conditions, with significant differences observed between study and complete conditions, and between copy and complete conditions.

-

Word Count: No significant differences were found in total word count or unique word count used to answer open response questions across conditions, suggesting that the amount of writing did not account for differences in retention scores.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that drawing can enhance recall of theoretical scientific concepts, with the drawing condition outperforming other groups on open-response retention tests. However, this advantage did not extend to multiple-choice or transfer tests. These results challenge previous research suggesting that instructor-guided visualization is more effective for retention. The improved performance may be partly attributed to increased engagement time, as suggested by our exploratory analyses of reading time and germane load.

Two key limitations warrant consideration. First, the laboratory setting may not accurately represent authentic learning environments where students are intrinsically motivated to learn, rather than participating for course credit. Second, certain visualization tasks may have inadvertently discouraged engagement—participants in the study condition could passively scan illustrations, while those in the complete condition reported finding the task confusing or elementary.

Future research should examine these visualization strategies in actual classroom settings, particularly in advanced science courses where abstract concepts are regularly taught. This would provide more ecological validity and help determine the practical effectiveness of drawing as a learning strategy in authentic educational contexts.

Acknowledgments

This research, conducted as an honors thesis at the Learning and Instruction in Multimedia Environments (LIME) Lab at UC San Diego (2018-2020), was made possible through the support of several individuals and organizations. I am particularly thankful to Dr. Geller for her exceptional mentorship, intellectual guidance, and continuous support throughout this project. Her insights significantly shaped both this research and my professional development.

I also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the LIME Lab members, whose constructive feedback during lab meetings and experimental design phases strengthened this work considerably. Special thanks to the UC San Diego Psychology Subject Pool for facilitating participant recruitment, and to all the students who participated in this study.