Tracing the Origins of Solar Wind

This project uses machine learning to analyze solar wind, trace its solar corona origins, and predict heliophysical events.

Introduction

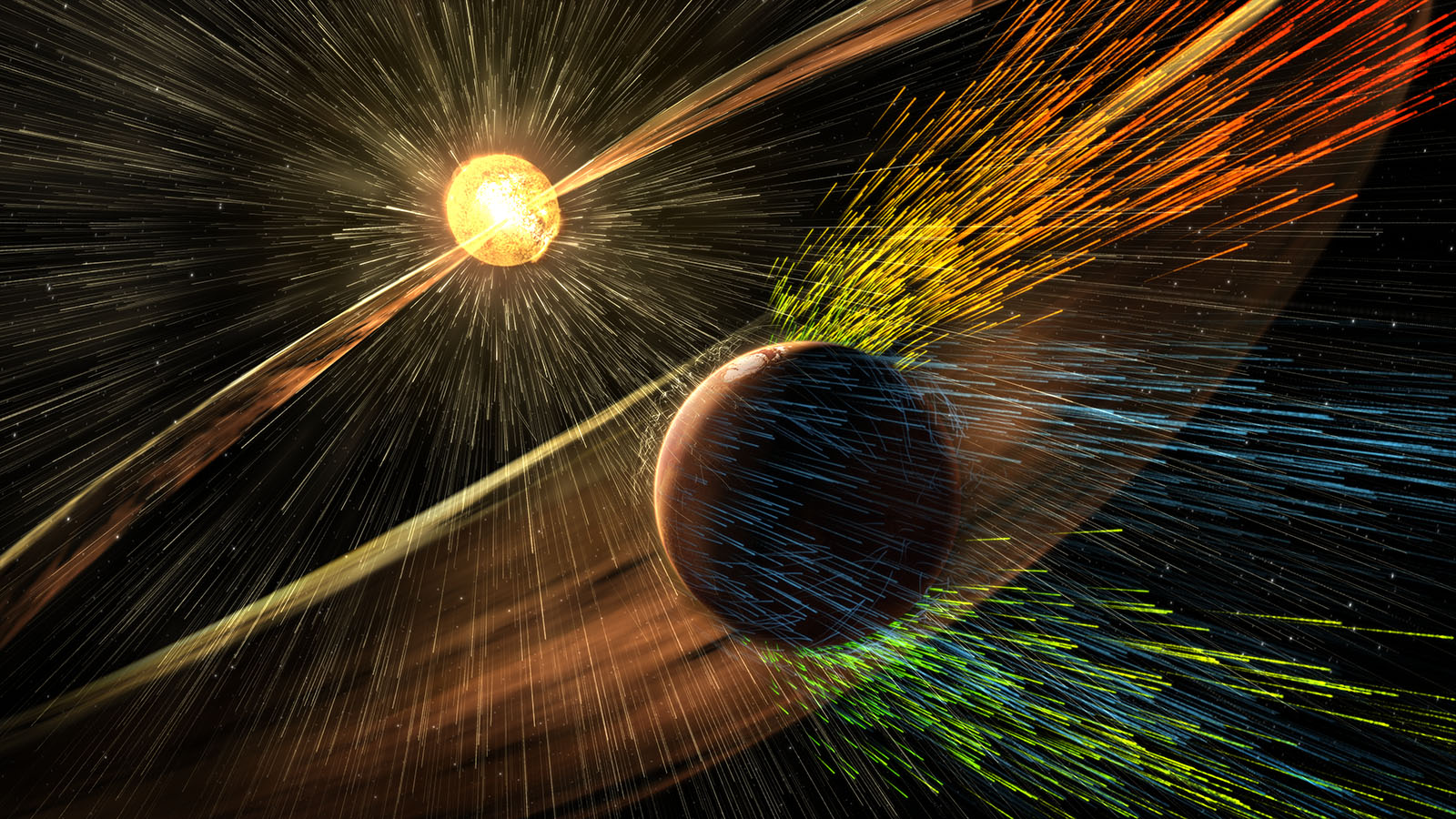

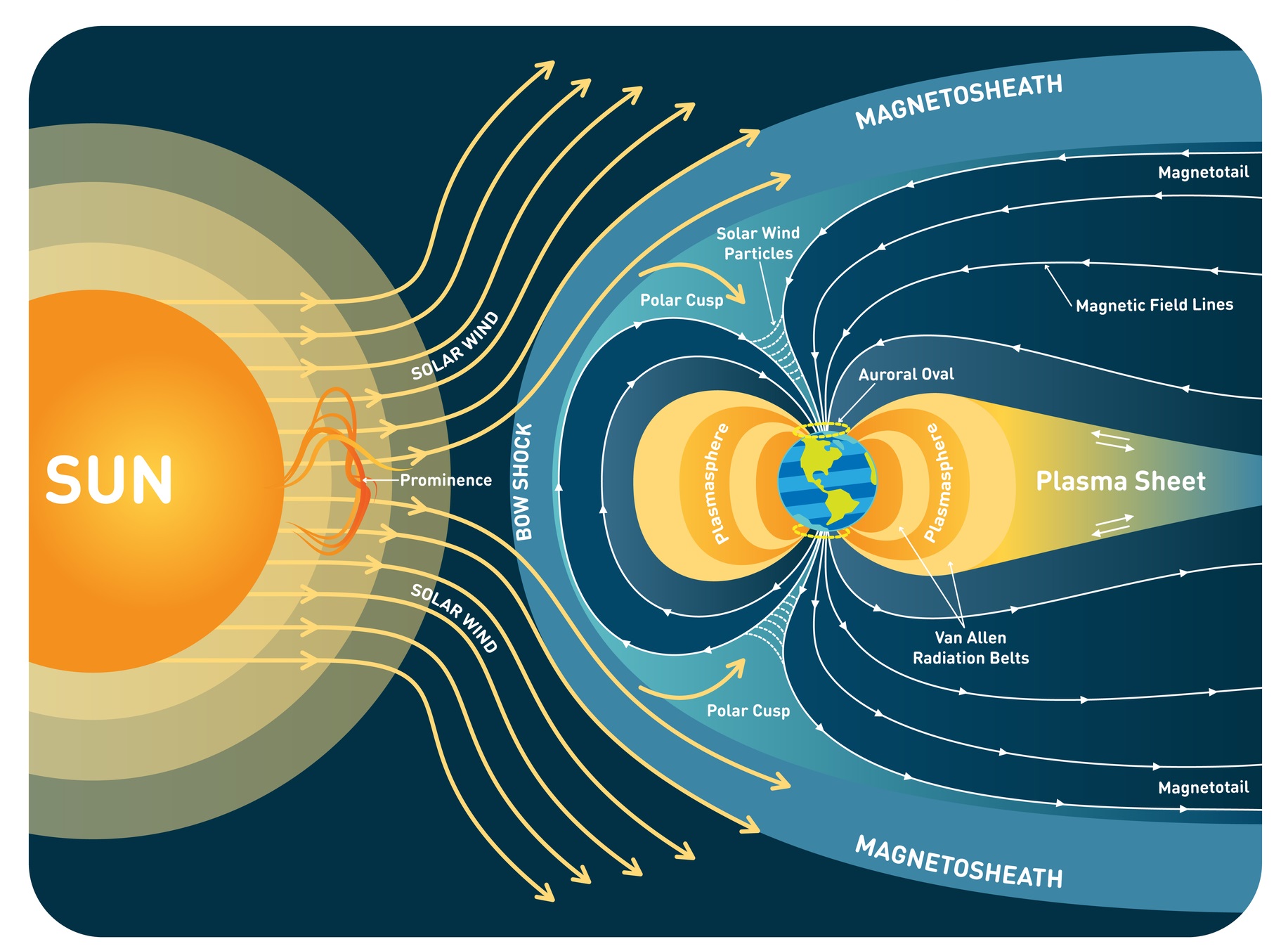

The solar corona, the Sun’s outermost layer, continuously emits streams of charged particles and magnetic fields collectively known as the solar wind. This high-energy stream escapes the Sun’s gravitational pull and permeates the solar system, forming the heliosphere. Periodically, solar disturbances, such as interplanetary coronal mass ejections (ICMEs), solar flares, and high-speed streams, propagate outward into the heliosphere. These disturbances can interact with the magnetospheres and atmospheres of planets, significantly affecting space weather - geomagnetic storms that can penetrate our atmosphere, threatening spacecraft and astronauts, disrupting navigation systems and wreaking havoc on power grids that impact Earth

The in-situ

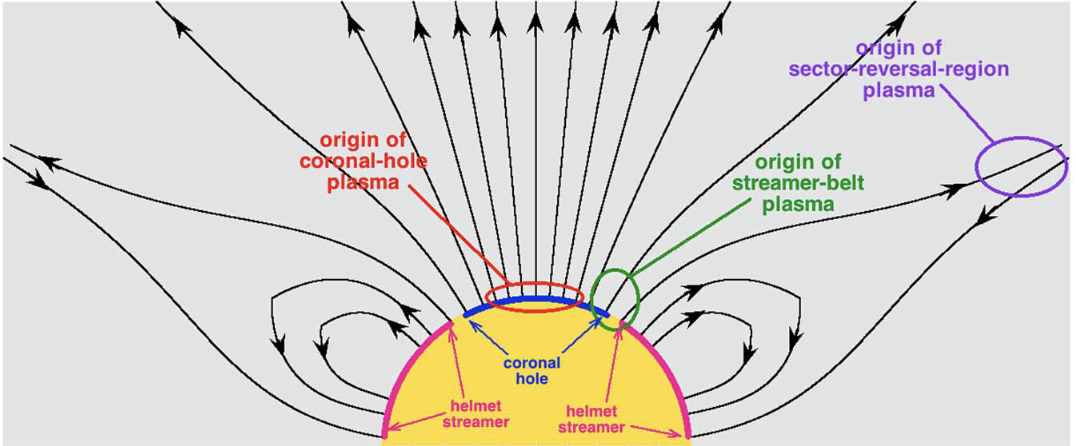

Solar wind can generally be classified into four major types: coronal-hole-origin plasma (CHOP), streamer belt plasma (SBP), sector-reversal-region plasma (SRRP), and ejecta (EJECT)

Traditionally, the classification of solar wind sources has relied on six in-situ measured physical properties: proton speed, proton entropy, proton temperature, ion charge states, and elemental composition. However, these measurements face challenges due to overlapping property values and the dynamic interactions of the solar wind with various elements of the solar system, which can obscure the definitive origins of the wind. Consequently, researchers often rely on subjective interpretation of continuous data distributions, making accurate categorization of the solar wind difficult. However, with improvements in Machine Learning, there has been a growing push to use machine learning to identify coronal features of solar wind and to predict future solar events. Here, we examine how machine learning has the potential to link the physical properties measured in-situ to the origin of the wind at the Sun.

Analytical Goals

Given the growing size and complexity of solar wind in-situ observations and the advancements in ML and AI techniques, it is crucial that we incorporate modern machine learning methods into the field of Heliophysics solar wind data analysis. Our research project aims to address the following:

- Apply dimension reduction method, such as PCA and TSNE to obtain informative solar wind in-situ data representation in the low-dimensional space. It will also provide better 2D/3D visualization support than traditional dimension reduction techniques.

- Apply feature selection methods on the solar wind observed parameters, to objectively rank the importance of these measurements.

- Employ clustering methods such as DBSCAN, OPTICS, etc., and their variants to objectively cluster the low-dimensional representation of the solar wind data, in order to better understand the potential differences among the categories caused by the different coronal origins.

Data Sources

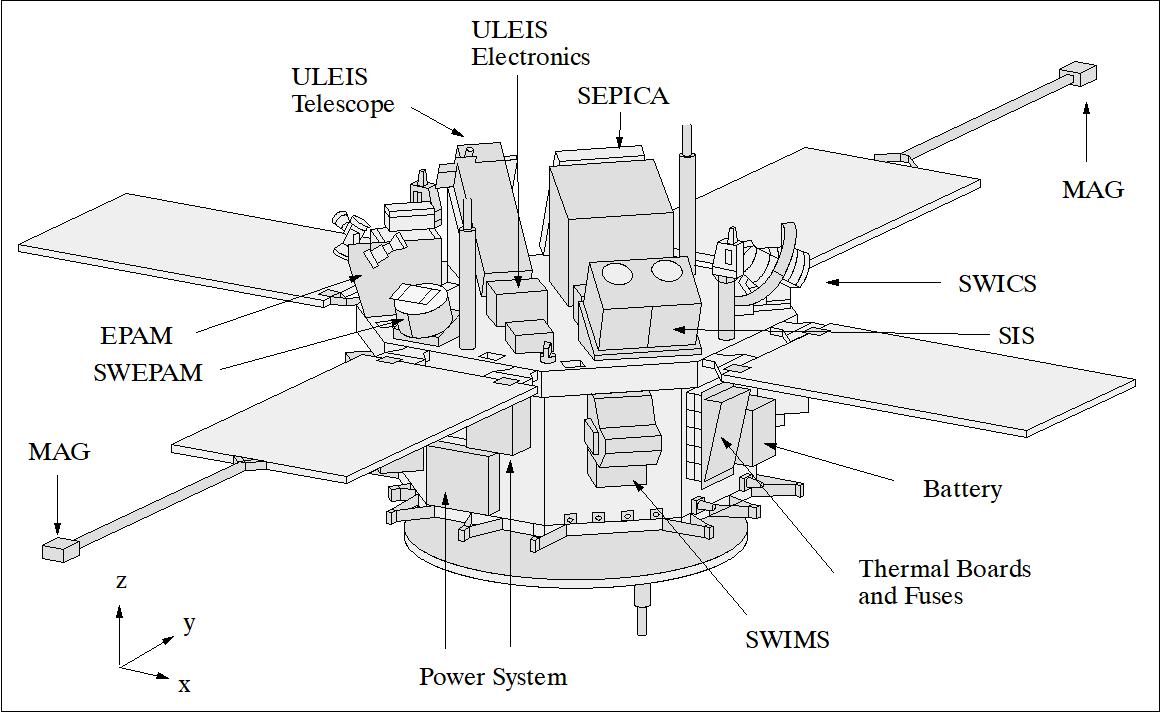

Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) Spacecraft Data

Launched in 1997, NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) mission captures and analyzes particles from solar, interplanetary, interstellar, and galactic sources. Its primary aim is to explore the connections between the Sun, Earth, and the Milky Way by examining materials expelled by the Sun. ACE data comprise in-situ measurements collected at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, about 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Earth — where the gravitational pull between the Earth and the Sun is at equilibrium

We focus on the data from four instruments of the ACE satellite:

-

Solar Wind Electron, Proton and Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM): measures rates of electron and ion flows with two distinct electrostatic analyzers with fan- shaped fields of view that use the spacecraft’s rotation to observe in all directions. The first one observes electrons in the 1 eV–1.35 keV energy range and the second one ions in the 0.26–36 keV energy range

. -

Magnetic Field Monitor (MAG): consists of a set of twin sensors measuring the three components of the interplanetary magnetic field at L1

. -

Electron, Proton, and Alpha-Particle Monitor (EPAM):

-

Solar Wind Ion Mass Spectrometer (SWIMS):

Data Wrangling

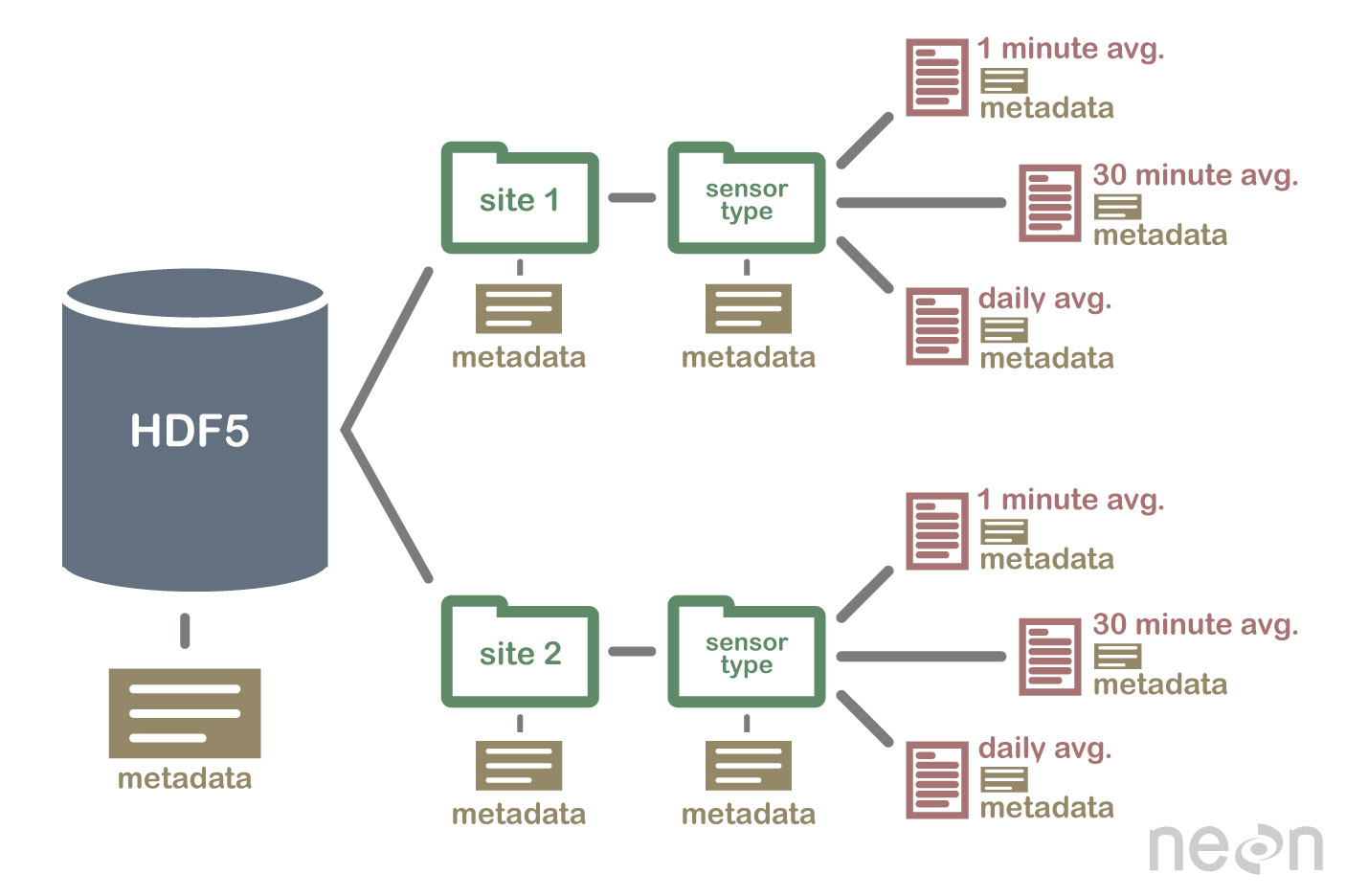

ACE data is stored in daily Hierarchical Data Files (HDF). We developed Python utilities to scrape, concatenate, and merge hourly data from multiple instruments (MAG, SWEPAM, EPAM, SWICS). We handled data quality issues by removing rows with bad measurements and transforming quantitative data using a logarithm base 10 and Min-Max scaling. This approach minimized biases and ensured uniform scaling across variables.

Feature Engineering

Using Zhao et al.’s classification scheme, we categorized solar wind into fast wind from coronal holes (CH), slow wind from non-coronal holes (NCH), and transient wind

Dimensionality Reduction

We employed PCA, FPCA, KPCA, and t-SNE to investigate solar wind data in low-dimensional spaces. While PCA handles linear data, KPCA and t-SNE manage non-linear data. t-SNE, in particular, preserves local relationships, making it ideal for identifying clusters. Our t-SNE analysis used the Barnes-Hut method to create 3D visualizations, while PCA, FPCA, and KPCA provided 2D insights.

Modeling

The precise point of origin of the solar wind can be traced back from spacecraft positions to the solar corona and the photosphere. Multiple authors have used a ballistic approximation coupled to a Potential Field Source Surface (PFSS) model to trace back solar wind observations to their original sources on the Sun. This is currently the best method to acquire the ground truth about the origin of the solar wind. Unfortunately, there is no central repository of solar wind origins for any space mission that we can use to train or verify our novel machine learning technique. For this reason we will need to use unsupervised learning methods.

K-Means: Spatially Separate Clusters

UMAP: Latent Features

Discussion

There are limitations to using in-situ properties to assign different types of solar wind to specific coronal sources. Firstly, the speed as a categorization metric is problematic. Solar winds originating from coronal holes are not always fast-speed wind; slow-speed wind could either have originated from small low-latitude coronal holes or from the boundaries of equatorward extensions of the polar coronal holes. Additionally, proton speed is not expected to be constant after the solar wind leaves the corona, as slow and fast solar wind streams can interact in “stream interaction regions” (SIR) or “co-rotating interaction regions.” The solar wind can still be accelerated after it leaves the corona within the expanding magnetic field. Therefore, solar wind speed is far from being an ideal separator to classify the solar wind into categories associated with different coronal regions.

Moreover, most in-situ measurements represent continuous distributions, with no obvious separation points in any of these variables to naturally divide them into different regimes. Identifying the solar wind whose in-situ properties are in transitory regions is subjective. Furthermore, solar wind in-situ properties are observed to be solar cycle dependent, including changes between solar maxima and solar minima and long-term effects across multiple solar cycles. Therefore, any criteria based on in-situ measurements will continually need updating along the different phases of a solar cycle and from cycle to cycle.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the ACE Science Center (ASC) for maintaining the ACE spacecraft data, and acknowledge the support of NASA’s National Space Science Data Center, the Space Physics Data Facility, and Edward C. Stone of Caltech, the Principal Investigator for the ACE project.

Additionally, thank you Dr. Liang Zhao for supporting our capstone project and providing Heliospheric Current Sheet (HCS) Indexes.